The idea for investigating residual impacts of mining disturbance on the deep sea floor was not new, but it first started for me in 2014 during a rather long journey from Ghana to Angola on another ship in another ocean from where we are now. With a period of enforced marine-inspired reflection ahead, I decided to see what I could learn from all the different disturbance experiments done that related to nodule mining. I spent the journey and several months after extracting and analysing the data contained in numerous scientific papers on the topic (results published here). One anomaly stood out - the iconic OMCO (Ocean Minerals Company) test in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ – the primary area of interest for deep-sea nodule mining). This test had been carried out under a veil of secrecy in 1979. It followed an unbelievable and staggeringly intricate CIA plot a few years before (1974) to recover a Russian nuclear submarine (project Azorian) using the same vessel (Hughes Glomar Explorer) under the cover story of deep-sea mining. Despite numerous records in reports and a few photographs of the OMCO collector vehicle, remarkably little was known of the test – even its location was secret.

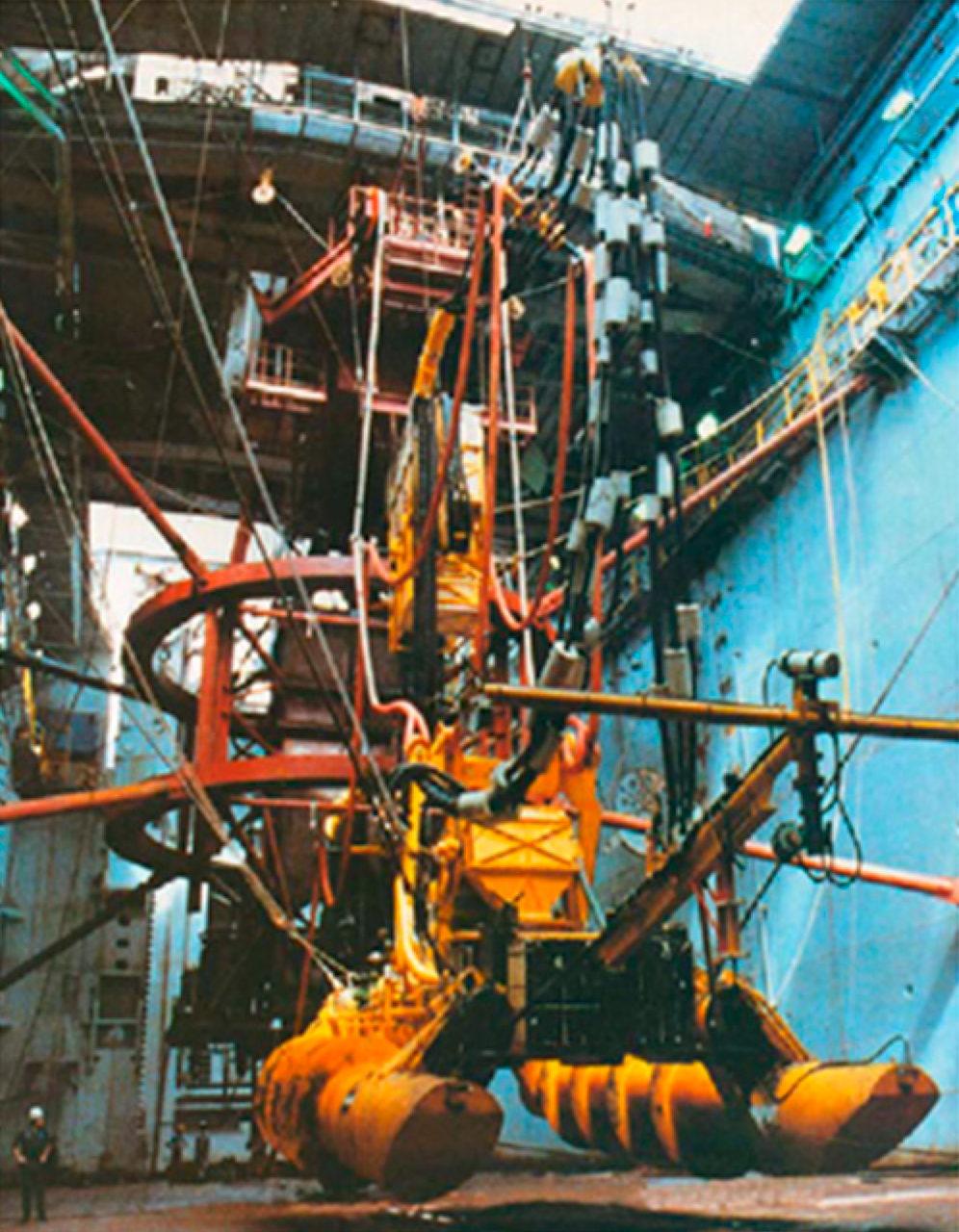

OMCO collector in 1979. Image from Cheng et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054572 reproduced under a Creative Commons licence CC BY 4.0

The OMCO test was clearly important scientifically, it would enable us to address, at least in part, a critical question facing scientists and policy makers – how long do the impacts of mining last and do they matter. The test was ideal, one of the first and last attempts to carry out realistic nodule mining. The test in March 1979 was remarkably similar to modern deep-sea mining plans with a seabed collector, riser to the surface and nodule collection to the ship. The next test done in this way was over 40 years later, with last year’s (2022) mining tests in the Clarion Clipperton Zone by The Metals Company (note the earlier GSR/BGR Patania II test in April/May 2021 focussed on the subsea collector and did not use a riser). The OMCO test was clearly important, but how to find it in an area of the CCZ of over 6 million square km?

Science begins in the library

During my search for information on mine tests in 2014 there was reference to several obscure reports with the promise of more information on the OMCO test. These were not available in any standard repositories. At the time I had assumed them lost and dismissed them as unobtainable. On a visit in 2015 to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Kingston, Jamaica, I was introduced to their archives held in the Satya N Nandan Library. This contains a gold mine of information collected with the help of organisational and individual donations of material made since shortly after the establishment of ISA in 1994. In the library, I found the clue needed – a map from a contemporary survey that included the location of the test site.

Map that showed the location of the test site. Note that this image has been modified from the original and digitally manipulated to remove locational information.

New exploration

At the same time as the map discovery, an extensive programme of work was happening elsewhere in the Clarion Clipperton Zone as part of the scientific projects (such as the EU-funded MIDAS project) and the exploration programmes of several contractors to the ISA. Together with a team of international science colleagues, we had been working to understand the seafloor environment in the first UK-sponsored ISA contract area in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, held by UK Seabed Resources (UKSR). UKSR has expertise in nodule mining from its parent company, Lockheed Martin. This is the same company that was a major shareholder in OMCO and its eventual owner.

With a small team of scientists (including those from the SMARTEX project team) we approached UKSR with the map and other information in the document to see if they knew more. The company used this information to locate and release a treasure trove of data from its corporate archives on the test. This was far more than we imagined and included tens of thousands of photographs of the seafloor taken before and after the test – all with annotation sheets, as well as maps, videos and transcripts made as the tests were taking place. From this, we knew we had a compelling idea for a new avenue of research. UKSR agreed to digitise this information and partner with us to provide what they had and try and secure funding to go back to the OMCO test site. Fortunately, thanks to the UK Natural Environment Research Council, you can see from this blog that we were eventually successful!