Transit

The target of our investigations is very remote, one of the furthest places from land on the planet. It is well over 2000 km from the nearest shore. The transit from our last port in Costa Rica to our first study area is over 10 days. What does a ship full of scientists do during this journey? It turned out to be very busy.

First of all, we prepared for the work ahead. This meant getting everything set up on the ship. All our gear had come from the UK either on the RRS James Cook itself or in one of the 12 shipping containers we sent from Southampton to Costa Rica in November 2022 (arriving just in time for the expedition in late January 2023). This equipment was craned onto the ship and then moved around the ship to the various laboratories using either cranes, carts or by hand.

Just a small selection of some of the scientific equipment that had to be unloaded ready for the expedition.

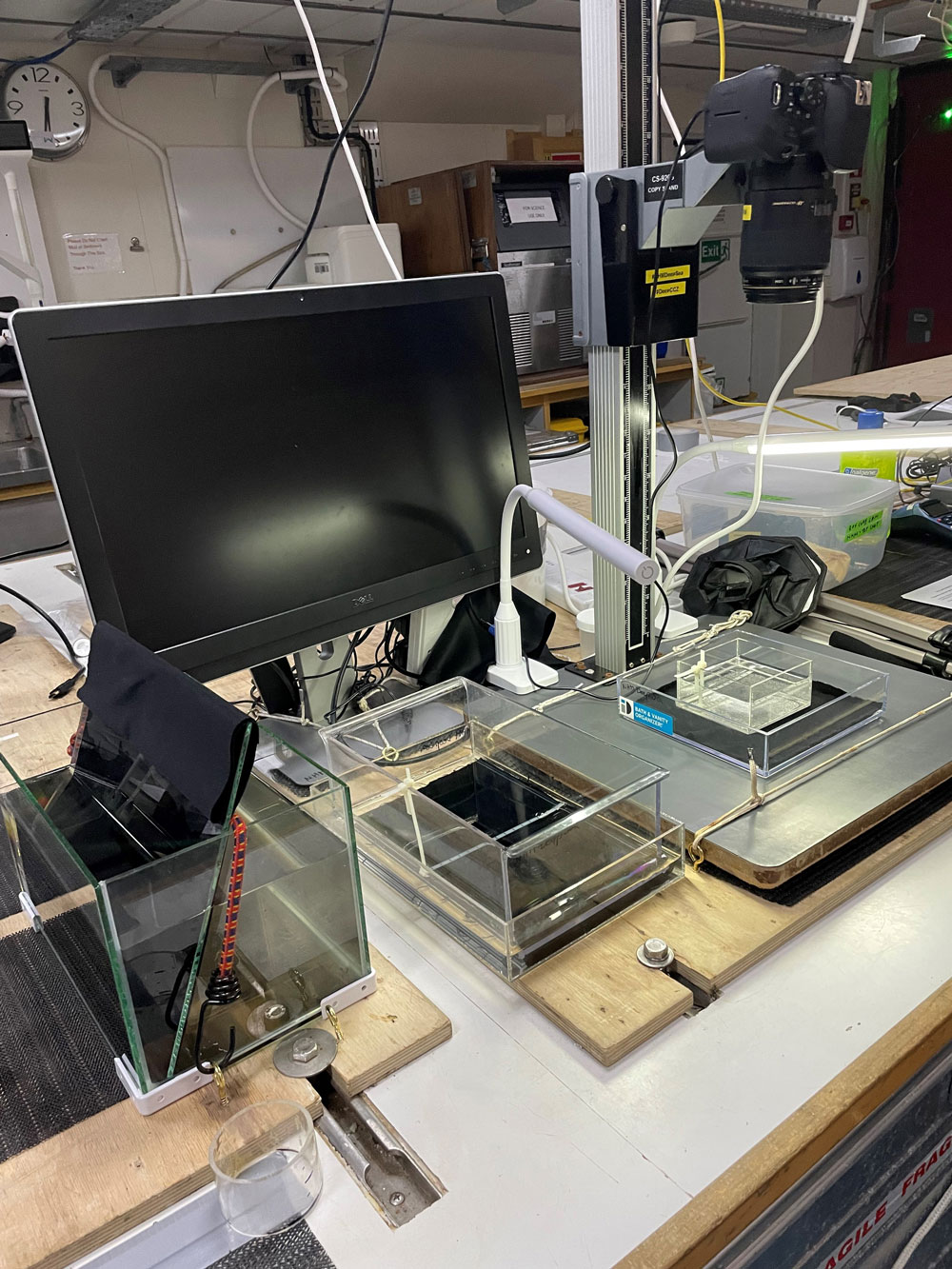

Setting up the laboratories has taken some time for everyone to get their equipment ready for 24-h a day sampling. As we are on a moving ship we have to secure everything to ensure it doesn’t fall over in bigger waves.

Microscope all set up for seagoing imaging of tiny animals

Artful lab decoration by the Natural History Museum team.

Last-minute preparations were also done at this time, making any missing parts to ensure that everything works well on the ship and we were completely ready. The ship carries a full workshop onboard to fabricate anything we were missing.

Ship’s workshop

The transit wasn’t wasted from a scientific perspective. We routinely collect oceanographic and meteorological data during our transits. We also map the seafloor as we go using the ship's multibeam sonar. These maps are contributed to the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans and help us fill in the blanks of the global map of the seafloor. The highlight of the underway observations was collecting data on the water movement as we passed through a several hundred-kilometer-wide eddy system. These eddies are relatively common in this area, generated by the Tehuano wind, blowing through the gap between the Mexican and Guatemalan mountains. These eddies move westwards at about 20 km a day and can even influence the currents on the seafloor at the Clarion Clipperton Zone.

Eddy currents moving from Mexico towards the Clarion Clipperton Zone

As well as preparing the equipment, the transit gave us an opportunity to get familiar with the ship and the safety provisions in place. This requires some refresher training. We have done lifeboat drills and fire drills to help familiarise everyone with what to do in an emergency.

Lifeboat practice – This lifeboat fits 52 people. Photo Catherine Wardell

Fire training in the sunshine

As well as catching up on other work, the transit also gave us an opportunity to see some wonderful wildlife. The ship is surrounded by seabirds, which feed on flying fish disturbed by the ship. We’ve seen whales, dolphins, turtles, squid and tuna already.

Seabirds on transit

Dolphins seen on transit. Picture from Mark Hartl.

Finally, the transit gives us an opportunity to get to know each other and share some of the amazing experiences of being at sea.

Watching another spectacular sunset in the Pacific