Scavenging amphipods are an important component of deep-sea ecosystems. They contribute to the detrital food web by scavenging dead fish and other ‘food-falls’, and they provide a food source for other deep-sea species. Because they feed on carrion, they are readily sampled using baited traps which has been done at PAP-SO intermittently since 1985. This has revealed a long-term change in the composition of the abyssal scavenging amphipod community which appears to link to upper ocean climate cycles.

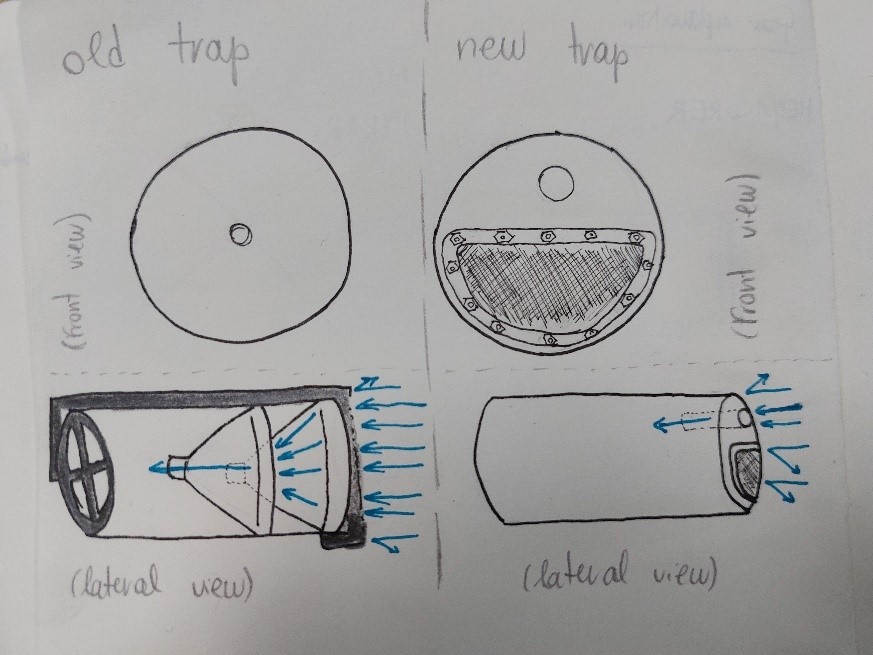

As a result of the amphipod trap mooring not releasing during the previous PAP-SO cruise (JC231) and being considered lost at sea, a new design is being used for the first time this year. The new amphipod trap consists of four grey plastic cylinders. The end of each cylinder is closed by a door containing a fine sieve-like mesh that allows the water to flow in and out of the trap during both the deployment and recovery of the trap whilst preventing the animals from escaping. The opening consists of a lid containing a mesh like the one present at the far end of the trap (although only covering over half the lid surface), and a cylindrical opening consisting of a 50 mm diameter tube. The traps are mounted onto a frame at two different levels, TOP and BOTTOM, and in two different orientations to mitigate the impact that the currents can have on the catches. As usual, mackerel is being used as bait.

We also attached to the mooring an additional trap we call the ‘blue barrel trap’, which as its name suggests is a large blue barrel which is 10 m above the other traps, to try and catch some of the larger, stronger swimming amphipods.

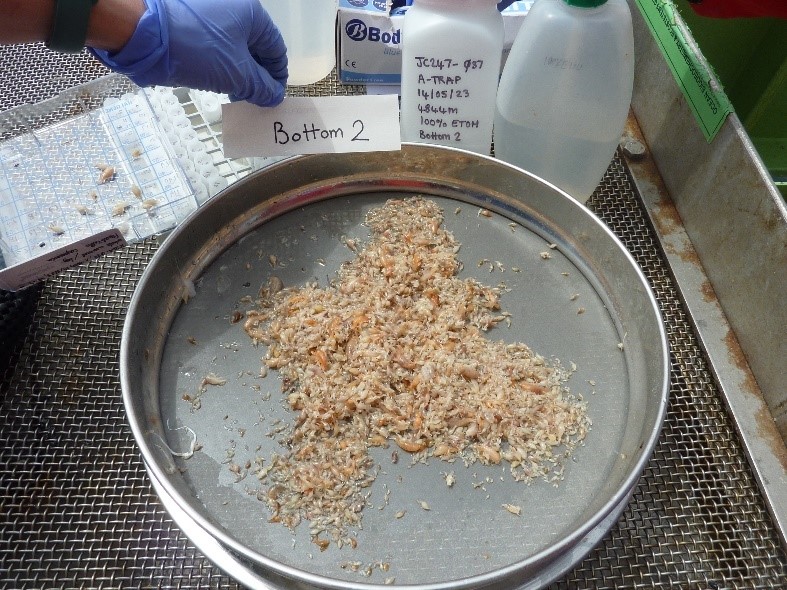

We had a modest catch on the first deployment (JC247-012), despite it being left at the seabed for over 46 hours. The catch wasn’t extremely small when compared to the previous campaign (JC231), but it was smaller than the catches obtained in previous years (e.g., DY103 in 2019).

The smaller catch and smaller specimens made us wonder if we might have under-sampled the station and if a lower number of specimens could be entering the trap due to the new design, in particular, the smaller trap opening. On the previous design, the trap opening consisted of a series of funnels that had a wide opening on the outside and that funnelled the specimens in. In comparison, the new trap had a single smaller opening and lacks the funnelling effect that potentially guided the specimens inside the trap.

To test our theory, two 50 mm holes (initially drafted by our mastermind, Brian) were drilled in either side of the original opening. To assess the impact of the new holes in the new trap, only one trap was modified per level. The amphipod trap was deployed two more times during the cruise.

The traps were recovered after being left at the seabed for slightly less than 48 hours. For both the second and third deployment, the catch on both top traps remained small, as expected, whereas the catch in the bottom traps was much more promising. Surprisingly, the trap that got the most specimens was the bottom trap where the opening wasn’t modified – which completely ruled out our theory! This suggested that more complex things like water currents might play a more important role in determining catches rather than the design of the traps – proving that the most intuitive answer is not always the correct one!

We also got some nice, big, colourful amphipods from the blue barrel trap. Most of the animals found in the barrel (all the larger ones), belong to the genus Eurythenes, more commonly known as 'giant amphipods'. They can grow to be as big as your hands!

The amphipod traps this year were a great example of what working on science and/or trying new equipment can be like. Developing any theory, piece of equipment, or carrying out any research project involves a lot of thinking, trying new things, and potentially lots of small failures and miss-interpretations – but we never let that stop us!

- Georgina Valls Domedel