Coming face-to-face with the deep-sea: the importance of natural history collections

By Jethro Reading

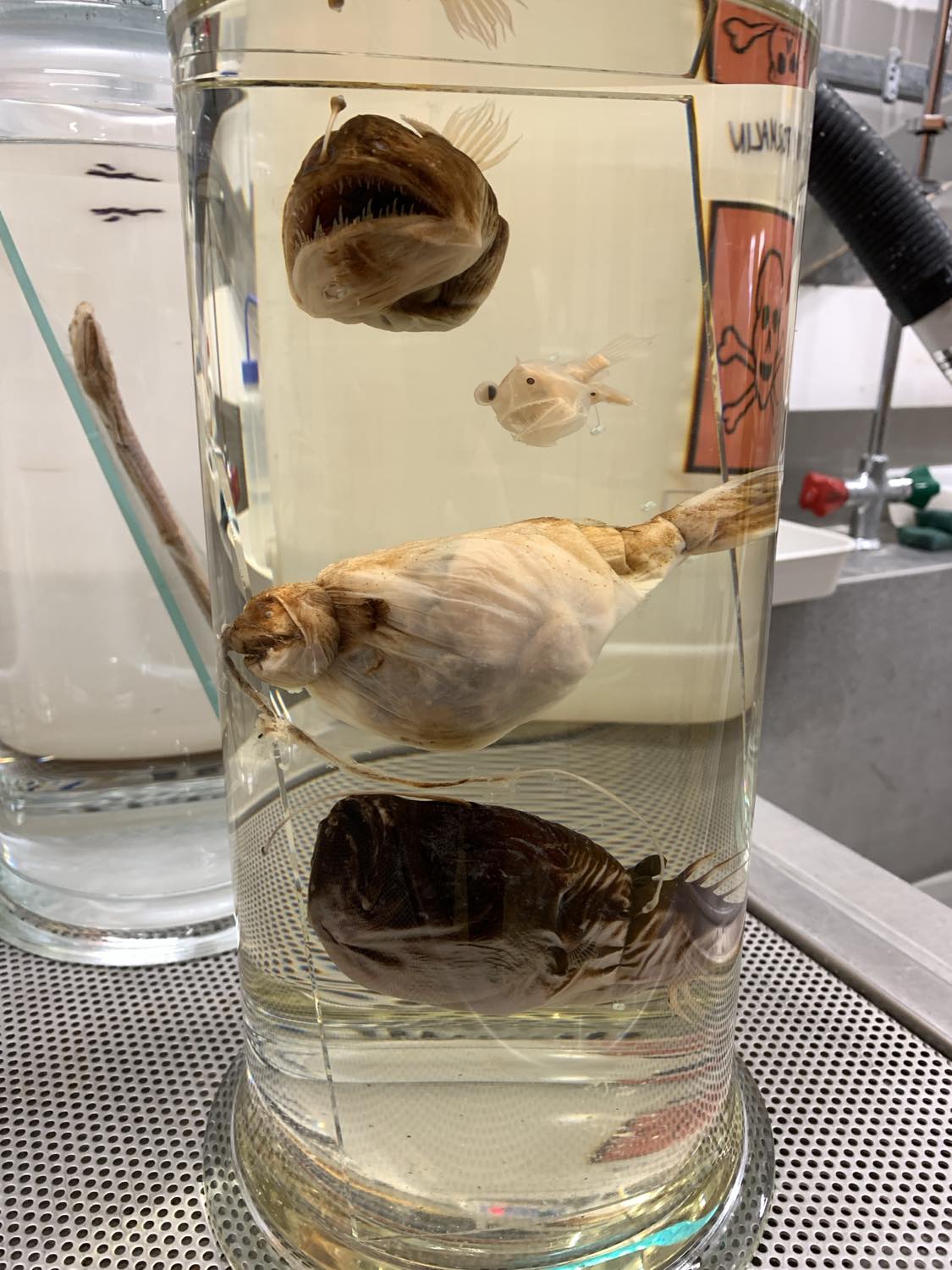

While I’ve had an interest in abyssal animals since childhood, my career as a deep-sea biologist has always been focused on physical specimens. On my first day as a student I walked past the library at the National Oceanography Centre and was fascinated to encounter an anglerfish staring at me from a jar of ethanol. As it turned out, that little spherical fish is just one of many bizarre critters stored at the NOC as part of the Discovery Collections [1].

The Discovery Collections contain nearly 100 years’ worth of specimens captured by British research vessels, including plankton from the Southern Ocean, midwater fishes from North Africa (which I was lucky enough to study for my MSci project), animals from the Crozet Isles in the Indian Ocean, and nearly every specimen collected from the Porcupine Abyssal Plain (PAP) since the time series began.

Working with marine specimens has given me great appreciation for the scientific value of natural history collections. A correctly identified and labelled specimen is a crucial piece of biodiversity data; proof this species lived where it did when it was collected. From repeated sampling at PAP, scientists have been able to track changes in these abyssal animals, most famously during the ‘Amperima event' [2], where between 1996 and 1999 the numbers of a small pink sea cucumber named Amperima rosea spiked. Going forwards, data from sampling will be essential to understand how climate change affects one of the largest habitats on Earth – indeed, there is already evidence of this in samples of amphipods (scavenging shrimp-like animals from PAP), which appear to change in response to climate signals [3].

This year we twice used a net to sample the seabed. The net in question is similar to those used by fishers for seafloor animals like langoustine but is much smaller, just 7m across (compared to commercial nets which can be wider than a Boeing 747!). The deployment and recovery of the net is one of the longest and most complicated for the ship’s crew, taking place overnight across 12 hours (of which the net is only on the seabed for two) and using more than 15,000m of steel cable.

Once recovered, we get to work cleaning, sorting, identifying, and preserving the catch. Of all the things that we do out here, this is by far the most time and labour intensive. In order to ensure that nothing is wasted, we have to be meticulous – not a single rock or worm or jellyfish is tossed back over the side. We also try to extract as much data as possible from the animals we collect – for example, this year I collected the ear bones of abyssal fishes, which contain information regarding the life history and ecology of the animals. Without these data abyssal fish are nearly impossible to conserve so this data is absolutely vital.

After the second trawl was processed, the entire benthic team was pretty wiped out from two days of hard, muddy, and occasionally quite smelly work. For many of us there was the awareness that this was just the beginning, though, as over the next few months specimens are identified and analysed. I for one can’t wait to get started!

Links:

[1] https://noc.ac.uk/facilities/discovery-collections

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0967064509000186

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079661120300574