When you think "marine scientist," your mind might drift to someone tagging dolphins or following the gentle rise of a surfacing whale. But there’s a whole other breed of ocean explorer – ones set on the more mysterious residents of the deep ocean.

Meet the amphipods: tiny, deep-sea crustaceans often nicknamed the ocean’s scavengers. Most are just 10 mm long, but some grow to 34 cm.

While not the most well-known marine species, these creatures play a big role in helping us understand how life survives – and adapts – 5,000 m beneath the waves.

Forty years of amphipod science at PAP

A key way we've been exploring these creatures is through the Porcupine Abyssal Plain Sustained Observatory (PAP-SO) – the world’s longest-running time series of life on an abyssal plain, operated by the National Oceanography Centre (NOC).

It all began in 1985, when, onboard the RRS Challenger, Mike Thurston led the first expedition to PAP pursuing a fascination with its curious crustacean residents. Find out how Mike got hooked on amphipods here.

It's a passion he has passed down – researcher to researcher – right up to today, with a new generation setting sail to continue the mission.

Carrying on a legacy – Dr Tammy Horton

One of those researchers is Dr Tammy Horton. When she arrived at NOC in 2001, Mike had officially retired – but hadn’t stopped showing up. Tammy was fresh from a PhD on isopods, but Mike's enthusiasm – and depth of knowledge for amphipods – set her on a new track.

“It made sense,” she says. “He was the world authority on deep sea amphipod taxonomy, surrounded by a wealth of literature and able to teach me everything he could about them, so of course we just started working together.”

Tammy dove in, juggling big research projects and motherhood, before the PAP time series came calling. When her first PhD student, Grant Duffy, took on the mountain of unsorted amphipod samples from PAP, they realised just how much untapped data they had on their hands.

“At first it was overwhelming,” Tammy recalls. “There were just so many samples. But that’s when I saw the potential.

“Over time, through student projects, building and comparing datasets, supported by students Zoe Gutteridge (2011-2012), Rhianna Vlierboom (2013)and Daiki Yamamoto (2017-2019), slowly we began to build up a picture.”

Tracking changes in the abyss

“It was then that the changes in amphipods at PAP became apparent. We were witnessing a switching of the dominant species. It was exciting to recognise what had only been hinted at before then.

“What surprised us was that these changes were occurring between two species of the same genus. When we started molecular work, we found there were more species than we realised, which is another story for another day.”

The result of Tammy’s work is not only reinvigorating the PAP amphipod time series, but also making it thrive – innovating in taxonomy and helping to discover new species and patterns.

Mentoring new scientists, emphasizing the importance of detail, observation and accuracy (as well as labels!), has also been a big feature of Tammy’s amphipod work. One of her latest mentees is Ben Walker.

Ben Walker: the next generation

Ben is diving into his amphipod adventure headfirst, including joining the latest PAP expedition, which will be his first time on the open ocean.

A masters student in marine biology and oceanography at the University of Southampton, Ben spends his spare time volunteering at the NOC-hosted Discovery Collections, under the guidance of Dr Tammy Horton.

What does that mean in practice? Hundreds of tiny amphipods, hours spent sorting samples from the deep, and a growing passion for creatures most people have never even heard of.

It all started thanks to a friend who was already volunteering with Tammy, cataloguing deep-sea specimens. Ben tagged along once – and never left.

“It’s inspiring seeing the diversity of deep-sea life preserved in the Discovery Collections,” says Ben. “From sea pens and giant sea spiders to deep-sea anglerfish – it’s like stepping into a vault of natural history.”

Some of those specimens are older than he is, collected during the very first PAP-SO expeditions in the 1980s. “There’s something special about working with them,” he says. “It really connects you to the decades of research and the people who made it possible. Now, being part of that process myself is a real honour.”

A fascination with scavengers of the deep

Just like Mike and Tammy, Ben has a fondness for amphipods.

“They’re so fascinating, from their diverse forms and structures (what we call morphologies in science) to the complexity of their body parts and the important ecological functions they carry out.

“I also love that I can spend a day in the laboratory, sorting amphipods from 4,800 m deep in the ocean abyss, and then head to a local beach or freshwater stream, turn over a few stones or bits of wood, and find them there too.

“Deep-sea scavenging amphipods are especially intriguing to me as they live in environments so far removed from anything I’ve ever experienced. I can imagine them scuttling and swimming about on the abyssal seafloor, seeking out a delicious carcass of sunken fish, then swarming all over the carcass until it’s nothing but bone.

“It would be cool to spend a day as one to see what they really get up to down there.”

A first time on the open ocean

While Ben will not be able to spend a day at the seabed, his participation in this year’s PAP expedition will give him an exciting opportunity to get more up close and personal with his amphipod friends.

“Knowing that you’re hundreds of kilometres from land, floating above nearly 5 km of deep water, will be truly humbling.

But what he’s most looking forward to? Seeing amphipods as they truly are.

“Preserved specimens lose their colours over time,” says Ben. “I’ve never seen deep-sea amphipods in their original, vibrant state. To see them fresh from the deep – with their true colours intact – is going to be amazing.”

Carrying the torch

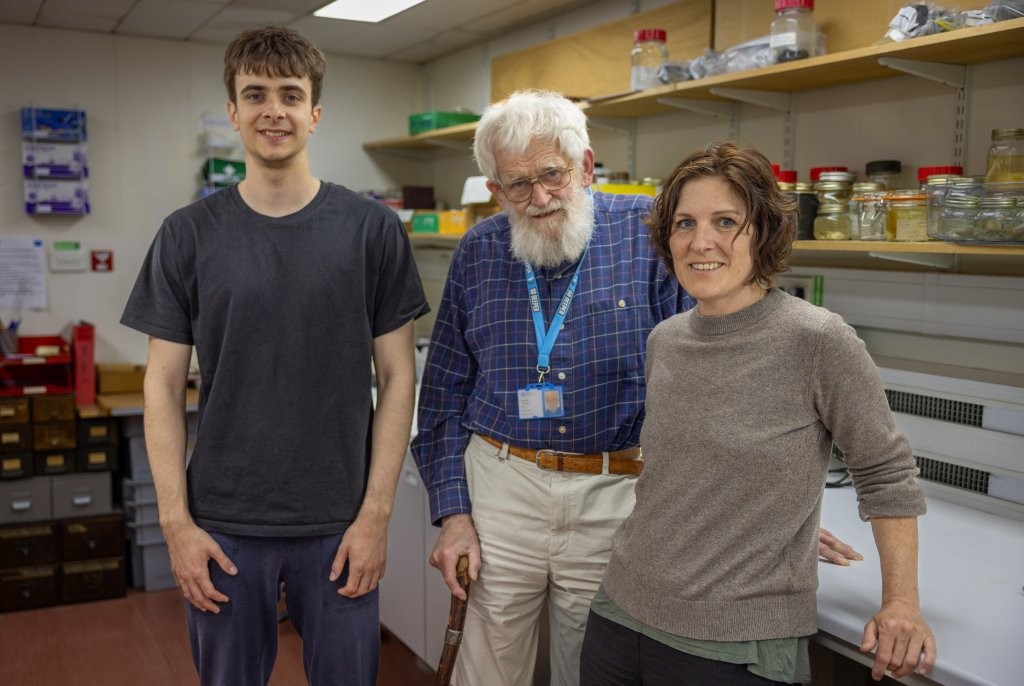

Tammy and Ben’s stories are part of a much bigger story – a long chain of knowledge passed down from researcher to researcher. From Mike to Tammy to Ben, it’s a legacy built not just on science, but on mentorship, observation, and care.

“I’ve learned that the real reward isn’t just the final dataset,” Ben reflects. “It’s the process – the sorting, the counting, the slow building of understanding. I’ve genuinely enjoyed every part of it. And it’s shown me how much dedication – and patience – marine science really takes.”

A circle completed

This year, Mike, Tammy and Ben will jointly name the newly described amphipod species, first found at PAP on that inaugural PAP expedition Mike led 40 years ago.

It’s a fitting tribute to their shared journey. Their work is about more than just cataloguing life in the deep; it’s about understanding how climate and ocean processes shape our planet, but also about passing on knowledge, skills and passion to the next generation.

As the RRS James Cook sets out once more, the story of PAP continues-one amphipod, one scientist and one generation at a time.

Dive deeper

Find out about how Mike got involved in PAP and his lifelong fascination with amphipods here.

Follow this year’s PAP expedition through our blog here.

Discover how science at PAP has helped to show how life in the deep ocean reflects changes at the surface: https://noc.ac.uk/news/three-miles-down-30-year-study-giant-amphipods-are-changing