PhD at Sea

By Lucy Goodwin

Studying the ocean can feel very abstract, as we are very disconnected from so much of it. This is why taking part in a research cruise is such an amazing experience for any marine scientist. As a PhD student studying deep-sea food-webs, a cruise to the Porcupine Abyssal Plain – Sustained Observatory (PAP-SO) is the perfect experience for me to get hands-on with my study area.

The PAP-SO has been regularly monitored by scientists at NOC for over 30 years and is longest-running abyssal time-series site on earth! It is therefore an ideal location for studying changes to the seabed through time - be it seasons, years or decades. For my PhD, I am exploring the relationship between body size and trophic level (i.e. position within the food-web) of animals living on the seafloor at the PAP-SO. These organisms live 4850m down, but rely solely on food produced in the surface ocean to survive. Plankton, fecal pellets, and other forms of carbon sink to abyss as Particulate Organic Carbon (POC; also known as marine snow). Unfortunately, the prevailing impacts of climate change are reducing the amount of marine snow reaching the abyssal seafloor – therefore my PhD research aims to identify which species rely on this marine snow and how what they are eating influences their body size. This will inform further research into how the animals are impacted by climate change and whether they will be able to survive it.

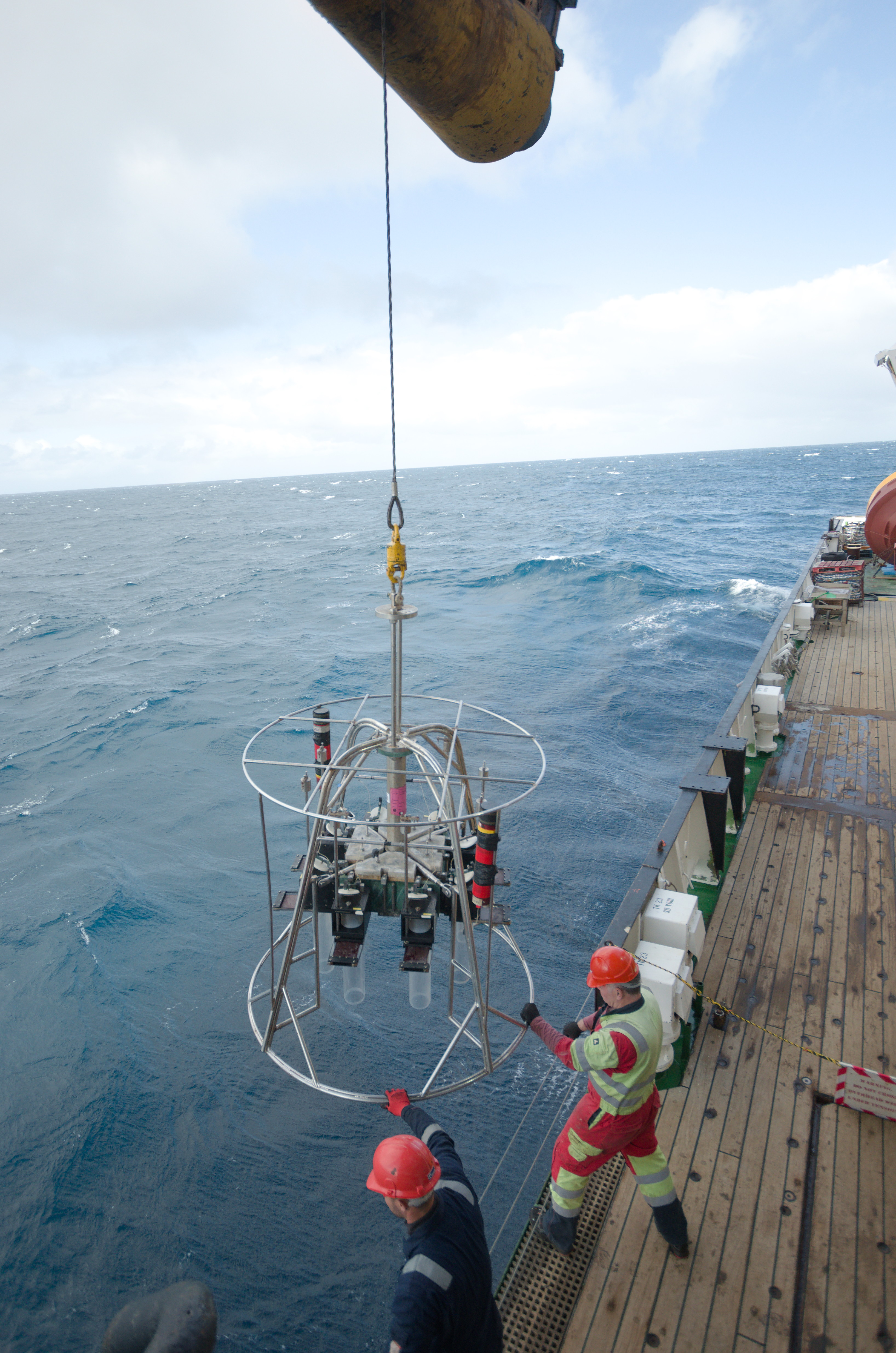

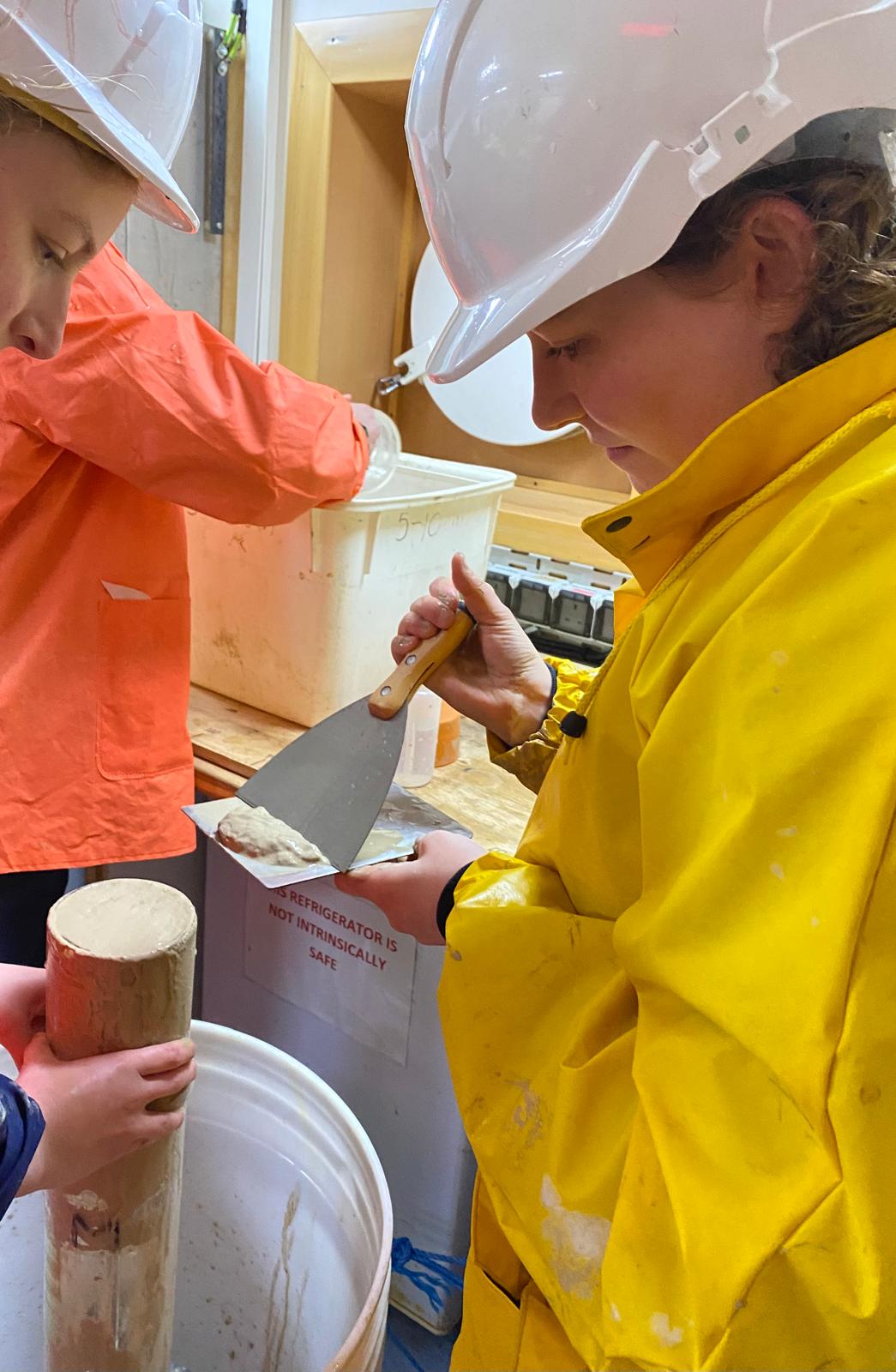

To answer these questions, I can collect all of the samples required from the PAP-SO through the activities carried out on board JC263. I am part of the Benthic Team, for which duties include processing the megacore (see the megacore blog from JC247) and benthic trawl samples, and assisting with monitoring the seabed photography – none of which would be possible without the incredibly skilled techs and crew members on board. I am able to collect my own samples from these processes to take back to The University of Liverpool for lab work and analysis. My baseline data (the bottom of the food web) consists of the top layers from the megacores, and sediment trap samples provided by the pelagic team. Some animals are collected from the seabed which I subsample for Stable Isotope Analysis to determine their trophic levels. The animals collected from the seabed are kept preserved in the Discovery Collections and are used for a lot of important scientific research, including monitoring seafloor biodiversity and identifying any changes to this.

Seeing my study animals in person is an amazing experience, especially when they live so deep in the ocean – it feels like a huge privilege to hold organisms that so many people will never see in person and potentially don’t even know exist! What’s even more exciting is seeing these gorgeous beings thriving in their habitats – which we are able to do this year with the HyBIS vehicle. This is a towed camera system that takes pictures at regular intervals and has a live feed up to the ship – allowing us to see the deep seafloor from the comfort of the deck. While I am not using this for my PhD work, the photographs will go towards many other exciting projects, and I can’t wait to see these animals live from their natural habitat!

Ultimately, being able to take part in research cruises for my PhD has been an unbeatable experience. I have been able to get hands on and connect with my study system, as well as meet other wonderful scientists and learn about their research too. Whether studying a PhD or not, I’d recommend any marine scientist to take part in a research cruise if given the chance.