As climate change accelerates, the need for research that takes in broader societal implications has never been greater. Rising sea temperatures, marine heatwaves, shifting species distributions and efforts to mitigate carbon emissions through initiatives like marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) all present complex challenges that will require interdisciplinary collaboration.

How do we balance scientific advances with ethical considerations, policy constraints and the lived experiences of communities that depend on the ocean?

How do we ensure research reflects not just technological feasibility, but also social responsibility?

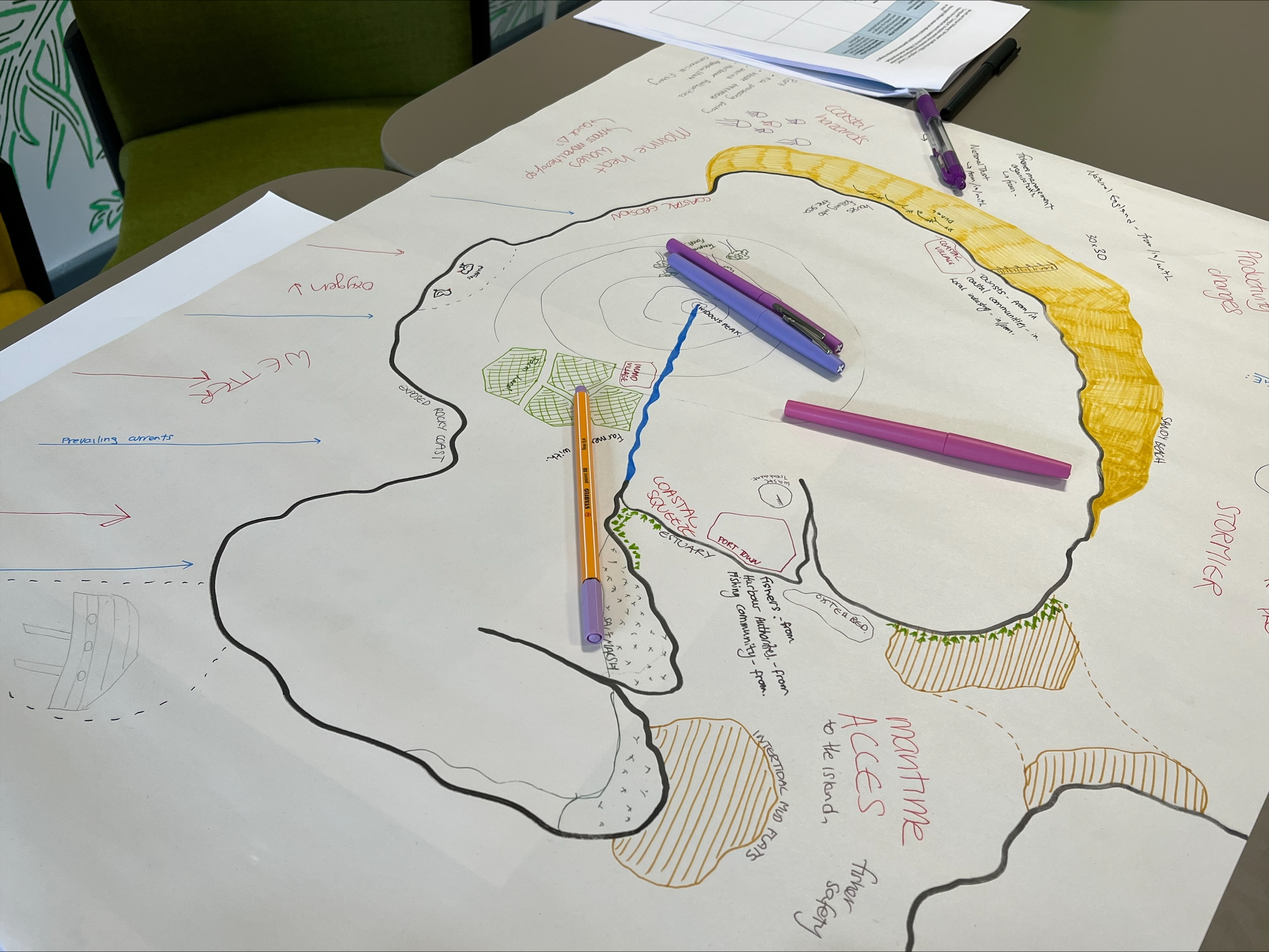

These questions were at the heart of the recent Socio-Oceanography Workshop at the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) in Southampton, where participants from as far afield as India, Brazil and the US, as well as Europe, gathered to explore the human dimensions of ocean research.

Discussions covered how researchers’ own views shape what they do, who to involve communities in participatory monitoring and what impacts the movement of marine species in response to climate change can have.

Going beyond involving communities in marine monitoring

One key theme focused on how to involve communities in monitoring the marine environment. Building trust to involve communities takes time and traditional funding structures often struggle to support long-term, interdisciplinary projects.

But when local communities are involved in data collection and even decision-making around what data is collected, it can help to improve science outcomes.

Local communities might have different ways that they would define ecosystem health—such as fish populations or visual changes—which could then be included alongside the initial metrics scientists want to gather.

This was borne out in a sample case study, where the goal was to involve the community in coral health monitoring activity. The project centred around testing a specific biogeochemical marker.

With community involvement, other markers of more importance to that community could also be integrated for a more holistic approach to understanding the wider health and importance of this habitat.

Marine species on the move

The workshop also examined the movement of marine species due to climate change.

This included a focus on the increasing presence of mauve stinger jellyfish in UK waters and the shifting distribution of seagrass, due to warming sea temperatures, rising sea levels and increasing extreme weather events.

Using a technique called ‘plural futures storytelling’, workshop participants explored different perspectives: human-centric approaches prioritising economic benefit, stewardship models balancing human and ecological needs and biocentric perspectives emphasising interconnectedness.

Discussions tended to show that short-term decision-making often led to dystopian outcomes, while more holistic approaches required deeper societal shifts.

A part of this session explored the emotional impact of species loss. The disappearance of key species, as seen in seagrass scenarios, can both affect entire ecosystems and evoke a sense of ‘ecological grief’.

Conversely, as species distributions change, community festivals could mark seasonal ecological changes—such as a ‘Jellyfest’, marking the annual arrival of jellyfish. Could this foster a sense of connection rather than loss of these new entrants in our coastal ecosystems?

What is invasive?

This led to the conventional idea of invasive species being challenged. With climate change accelerating species redistribution, traditional labels of ‘native’ versus ‘invasive’ are becoming inadequate.

The Solent, a hotspot for non-native species, reflects the dynamic nature of marine environments. Rather than demonising species shifts, some emphasised the need to view them as part of ongoing planetary changes.

Marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR)

Another key theme was an exploration of how different perspectives within mCDR research affect that research and outcomes. This used fictional personas to represent a range of views, from a synthetic biologist developing algal strains to an anthropologist sceptical of mCDR’s effectiveness.

The exercise highlighted the fluid nature of research roles—scientists often shift between being pure researchers, issue advocates or intermediaries depending on context.

The challenge of finding a truly neutral ‘honest broker’ was evident, but the emergence of various advocacy roles underscored the complexity of ethical research.

A coming together

A common theme throughout the workshop was the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and inclusive participation. Whether through persona-driven policy research, community-integrated monitoring or future scenario planning, ocean research must remain adaptable and inclusive.

Through the Socio-Oceanography Workshop, we underscored the importance of fostering dialogue between science, policy and community knowledge, ensuring marine research benefits both people and planet in an era of rapid environmental change.

Dive deeper

Socio-Oceanography is a NOC cross-cutting theme, aiming to promote integrated marine research inclusive of strong social science that is required for the delivery of sustainable ocean futures.

Our Socio-Oceanography Workshops are an annual national workshop series that facilitates collaboration between marine social and natural scientists, organised and hosted by NOC in collaboration with the Marine Social Science Network.