The ocean is an incredibly rich and diverse place, covering 70% of our blue planet. But while we’ve been exploring it now for centuries, we’re actually discovering more new species in it than ever before.

According to the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), since 1758, the average overall discovery rate – based on the data it contains – has been 1,254 marine species per year.

Yet in the 15 years to 2021, the number rose to 2,239 marine species on average per year.

Although we’ve discovered so much already, even more marine species descriptions are being made*. What’s more, there’s plenty more to discover, explains Dr Tammy Horton, an expert in deep-sea taxonomy, ecology and biodiversity at the National Oceanography Centre (NOC).

Dr Horton manages the Discovery Collections at NOC – the only collection consisting solely of deep-sea and open-ocean invertebrates in the UK, with samples dating back to 1925, collected in the Southern Ocean by the first Royal Research Ship, RRS Discovery.

She’s also an active deep-sea biodiversity researcher and taxonomist, helping to bring to light previous unknown deep-sea species, while also working on WoRMS as an editor of the World Amphipoda Database and the World Register of Deep-Sea Species.

“It’s estimated that there are more than 2 million marine species and that number could be much higher,” she says. “Only about 11% of that estimate, or about 250,000, have been properly described. Our goal with WoRMS is to document how many there are.”

An international collaborative project

Launched in 2007, WoRMS is an international collaborative project to provide an authoritative and comprehensive list of all published names of marine organisms.

Editors working on WoRMS, including Dr Horton, recently took a deep dive into the data it holds to explore rates of discovery over the decades and even centuries.

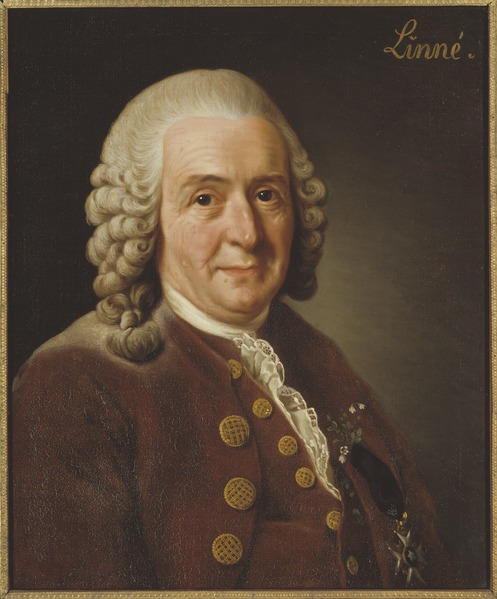

“The data it contains goes right back to and even before Linnaeus, the famous Swedish botanist who devised the formal system used to name and classify living organisms,” says Dr Horton.

“He is still the person responsible for describing the most marine species within a single publication and very few marine species descriptions predate his work from 1758 – nearly 270 years ago.”

Dr Horton co-authored a recent paper outlining the results of the exploration into WoRMS’ data.

1977: a high point, for marine species descriptions

“An interesting fact that our study found was that the highest number of new marine species descriptions was made in 1977, when 3,695 were introduced to science,” she says. “We have a prominent American marine biologist Dr Irene McCulloch to thank for this.

“She was responsible for a single publication that year which described 1,727 species of Foraminifera as new to science. While this would have been based on a numbers of years work, it’s still an impressive achievement.”

Some species are harder to identify than others, although they are plentiful and diverse.

“Digging back into history, the first marine fungi species were not described until 1783, the first protozoa in 1830, the first bacteria in 1836 and the first archaea in 1880,” says Dr Horton.

“Discovery rates for some of these types of tiny organisms remain small. Just eight marine species descriptions of archaea, a group of tiny single-celled microorganisms, were made between 1998 and 2007, for example.

“So there’s still a lot we have to discover…

“While animals are easier to find, we’re still finding lots of them. In fact, 2008 was the first year when more than 2,000 were described.

“We think this is at least partly due to the Census of Marine Life, a major international collaboration over 10 years involving 2,700 scientists.”

The achievement so far is fantastic. Significant progress has been made over the last 17 years WoRMS has been running. But it’s still far from complete.

1,000 species by 2030

“One area we know that hosts a multitude of marine species new to science, but is not very well explored, is the deep sea – or depths greater than 500 m,” says Dr Horton.

“They’re harder to reach and there’s a lot of it, which makes it challenging to explore.

“Even from the most studied deep-sea regions, such as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the central Pacific Ocean, specimens have been identified and are available within science organisations or museums. But they are currently undescribed, so the wider world doesn’t know about them.”

NOC scientists, through projects such as SMARTEX, are investigating how many species there are in the CCZ – and identifying that there are thousands that are new to science.

But that’s not stopping the international community trying. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) launched the One Thousand Reasons campaign in 2023.

Its aim is to add the description of at least 1,000 species new to science in areas beyond national jurisdictions to WoRMS by 2030.

Learn more here.

But it’s all also a voluntary effort, that means keeping up with and describing new discoveries, with only so many taxonomists able to do it, and it’s not always easy.

On average, 422 edits on WoRMS are made daily, which roughly translates to an addition or improvement to the content of WoRMS every three minutes.

More than 300 volunteer editors across 226 institutions in 45 countries contribute to WoRMS today.

Read the full paper here.

Find out more here.

*Since the introduction of Linnaeus’ system.