by Dr Alycia Smith, Science Co-ordinator at NOC

This October, I’ve been thinking about how my mixed heritage has shaped my journey – both in life and in science. So, I’m sharing a few personal stories, some informative stats, and a bit of what Black History Month (BHM) means to me.

In Two Minds

Coming from a predominantly white family (pictured below), English culture had a huge influence on my upbringing and provided a community with little to no shared experience of racism for me to discuss with others. I had to go on my own equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) journey, unlearn certain unconscious biases I picked up during my upbringing, develop an understanding of systemic racism and I am still learning. It is interesting to review your life and its events from a culture and race perspective and see all this new detail – positive and negative – come to light.

Of course, race is not the only factor in this journey. We are intersectional beings, and I must stress the importance of considering more than one facet within our lives: I am also a woman, cisgender, heterosexual, from a working-class background, plus size, neurodiverse, a first-generation higher education student, and second-generation immigrant. To some, these labels may seem counterintuitive (i.e., putting me in a box), but they help me to see where my journey is different, why it is different, and how those differences impacted my path to here, my life today, and my plans for the future. They also help me to connect with relevant communities and those with similar experiences; a problem shared is a problem halved, right?

While these aspects of my identity shape my lived experience, they also intersect with broader systemic patterns such as those in academia and research. This got me thinking about the numbers behind it all –does this play out beyond my own experiences?

The 0.4 / 1.2 / 3 / 4% Club?

My community, Mixed ethnicity students, made up 4% of the UK postgraduate research (PGR) community in 2022-23 (74% White; UKCGE, 2024) and 4% of the 2023-24 NERC studentships (46%; UKRI Equalities Monitoring, 2025). Between 2016 and 2019, 245 out of nearly 20,000 UKRI PhDs were awarded to us (students from Black or Black mixed backgrounds; Williams, Bath, Arday and Lewis, 2019): that’s just 1.2%. Our overall satisfaction was 3% lower than for White students, and we were 3% more likely than the sector average to consider leaving our programme, with a lower level of peer and pastoral support as the likely cause (Advance HE Ethnicity and Postgraduate Experience Report, 2020).

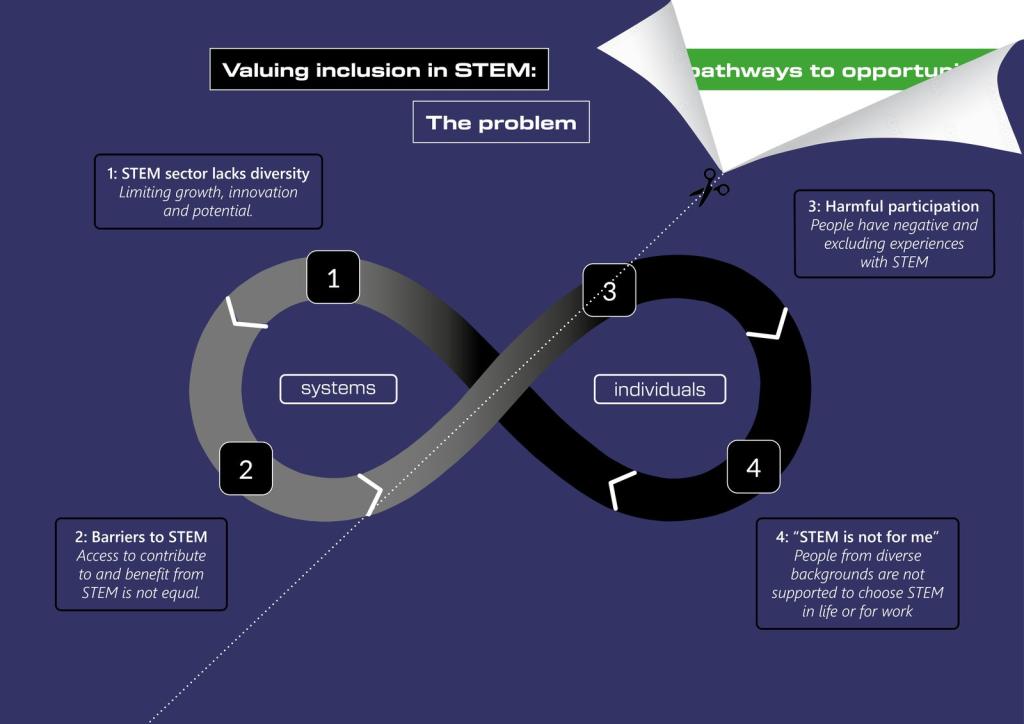

In fact, between 2010 and 2023, my community has consistently reported the lowest satisfaction rates of any ethnicity in UK higher education (Garrett and Ridgway, 2025). In grant applications, we would be 4% less likely than the White community to receive UKRI funding as a principal investigator, and on average would receive £100,000 less than them (UKRI Equalities Monitoring, 2025). These numbers represent a system that restricts access to and limits progression through the career pipeline for minoritised communities, limiting representation in the field and further leaving us more likely to either not even consider pursuing or failing in the career (Figure 1, Association for Science and Discovery Centres, 2025).

However you look at it, the statistics speak for themselves. I share these not to encourage pity or discourage my community from a research career, but as a starting point for an investigation that people, globally, are exploring: Why is this the way it is? For me, existing somewhere within these tiny percentages as a White and Black African person, I recognise the importance of quantitative reporting on the structural inequality.

Yet, there is so much about our experiences that aren’t contained within these reports: each of us come bearing our own personal statistics. For instance,

- 13 muscles: the estimated number of muscles it took to force a smile when a fellow scientist reassured me that there would be spare shampoo on a research vessel if I ran out.

- 0.94°C: the approximate temperature my cheeks rose by after blushing as someone shouted ‘nice! Rasta!’ when they saw I had braided my hair.

- 5 seconds: the length of time I felt confused after being asked where I learned English, because it was really good.

- 0 people: the group size of role models that I could relate to growing up (and now, really, unless I count myself?).

If you find yourself reading the above anecdotes and feeling confused, let me explain.

My hair is like that houseplant you can’t keep alive – one wrong condition and it’ll give up on you! Most black hair types cannot withstand hair products with sulphates, parabens and silicones, causing drying and product build-up, and I’m guessing the bottle sitting in the ship’s store would be a triple offender. Rather uninterestingly, I learned my English in England as it is my first and only language. Oh, and lastly, the Rastafarian community prefers dreadlocks!

Why is this important? Because it highlights that there is no one size fits all when it comes to non-white experiences and inclusion. Growing up, I didn’t see anyone who looked like me in the spaces I aspired to be in – no one to show me that I belonged in science or academia, or even on a research vessel. I’ve had to learn to become my own role model: to celebrate my wins, advocate for myself, and pave a path that others might one day follow. It’s not always easy, but it’s powerful and necessary.

What does Black History Month mean to me?

To me, BHM is a time to reflect, celebrate and educate ourselves. Where has my mixed heritage influenced my life in a positive or negative way? What lessons did I learn from those events? Where can I advance my knowledge of accessible and inclusive practices that go beyond my own experience? What can I do to foster knowledge exchange and support the communities within my reach?

We Brits love a status quo, but recently, I’ve recognised that muddled in with all the barriers to progress – closed-mindedness, resistance to change, a lack of empathy, misinformation spreading like wildfire – change is starting. Where I used to sit alone, tables of allies are filling as they take their seats beside me and clock in for the October shift. Year by year, I find myself less overworked (People of Colour [PoC] are historically over-relied on for BHM efforts; google ‘Black tax/fatigue’) and more supported. PoC work twice as hard to reach positions in which they feel they can speak out – sometimes risking it all in the process. As someone with a mixed background (50% privileged, if you will), it is imperative that we use our voices and influence to provoke support and understanding in our local communities (and beyond, if you can).

Roger Arliner Young said “not failure, but low aim is a crime” – I strive to live by this thinking. We will get things wrong, and things will be tough, but it is infinitely worse to not try at all. For us, celebrating Black History Month doesn’t end on the 31st of October. Allyship is everywhere, in the small and big actions, with neighbours to global communities: what actions could you take?